Article and art by Riel A. A. Diala

20 March 2021

Years ago, standalone cinemas dominated the Philippine entertainment market. Filipinos went to cinemas to see movies as a favorite pastime or source of amusement. These establishments were prevalent in numerous Philippine cities, and Manila is no exception. Movie theaters lined prominent thoroughfares such as Rizal Avenue, Escolta Street, and Quezon Boulevard. However, with the changing environment, technological development, and the evolving preferences of Filipino consumers, these witnesses to the country’s cinematic history have since become derelict and forgotten.

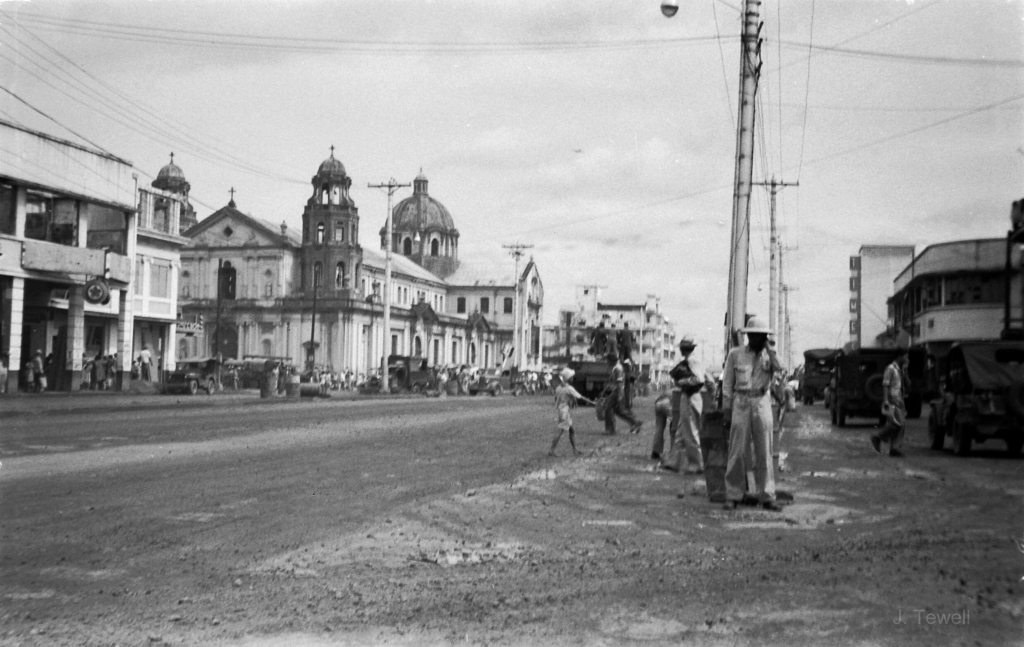

Photo from the collections of John Tewell, Flickr (2021).

According to heritage advocate and author Isidra Reyes (2020), cinema in the Philippines commenced with the initiation of the first electrical power plant in Manila, which was built by La Electricista in the 1890s. With the advent of a new energy source, it became possible for film projection equipment to be imported into the country. Along with the introduction of a new medium of entertainment came the first presentation of mostly French short stories at the Salon de Pertierra – the country’s first movie-theater along Escolta in Binondo.

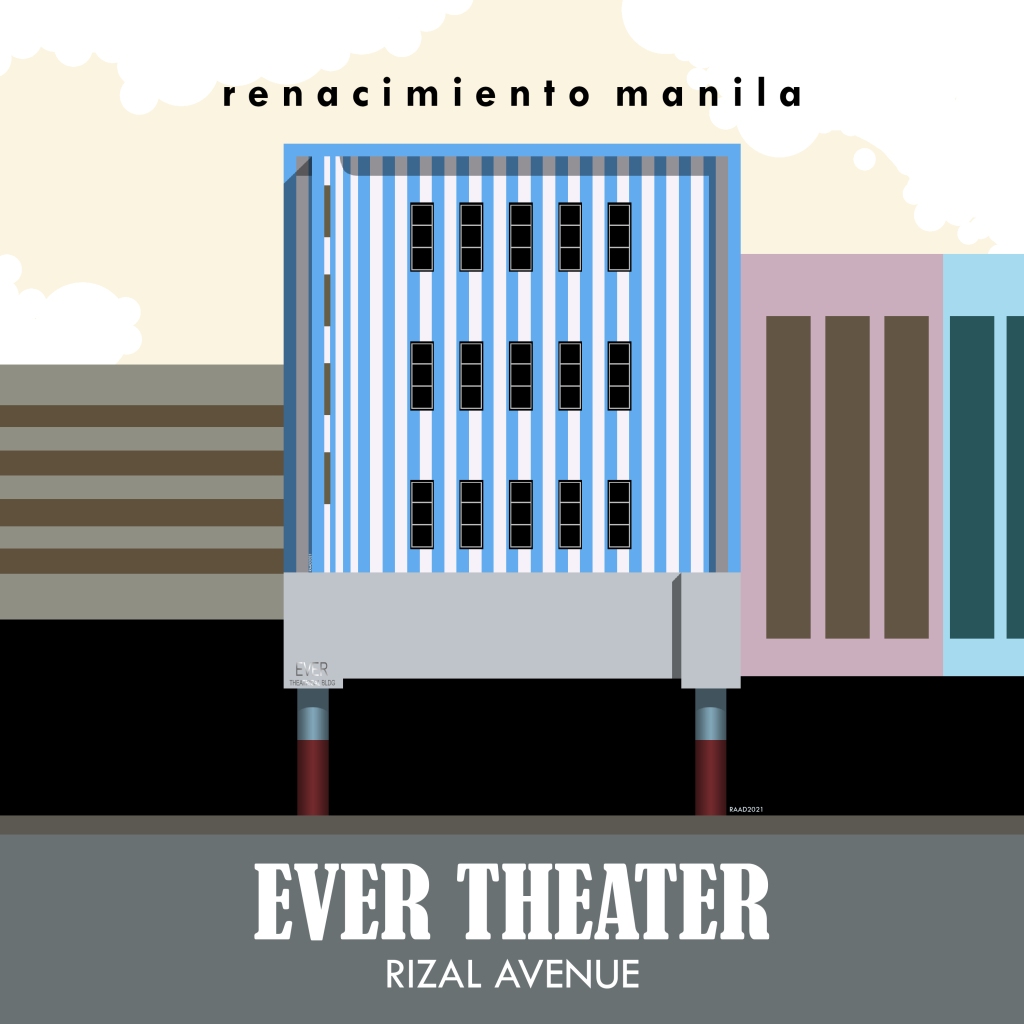

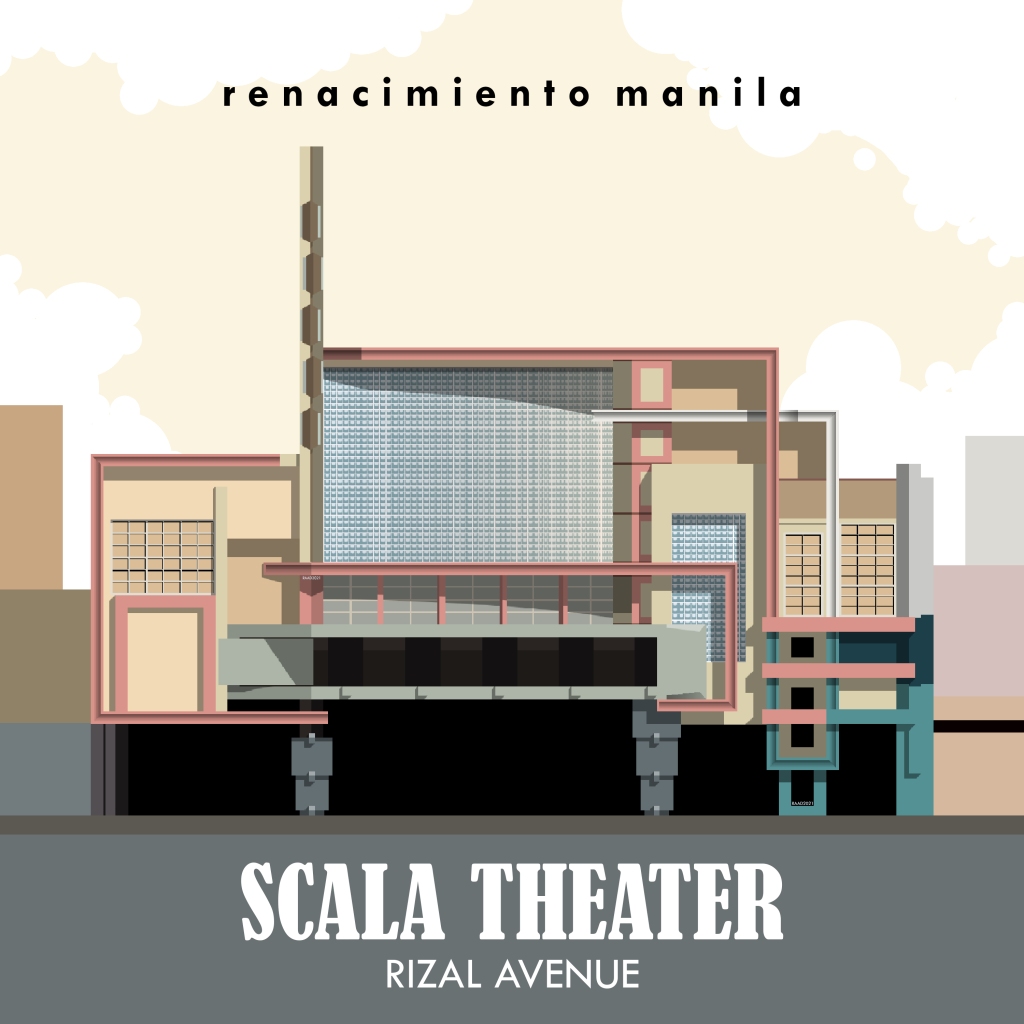

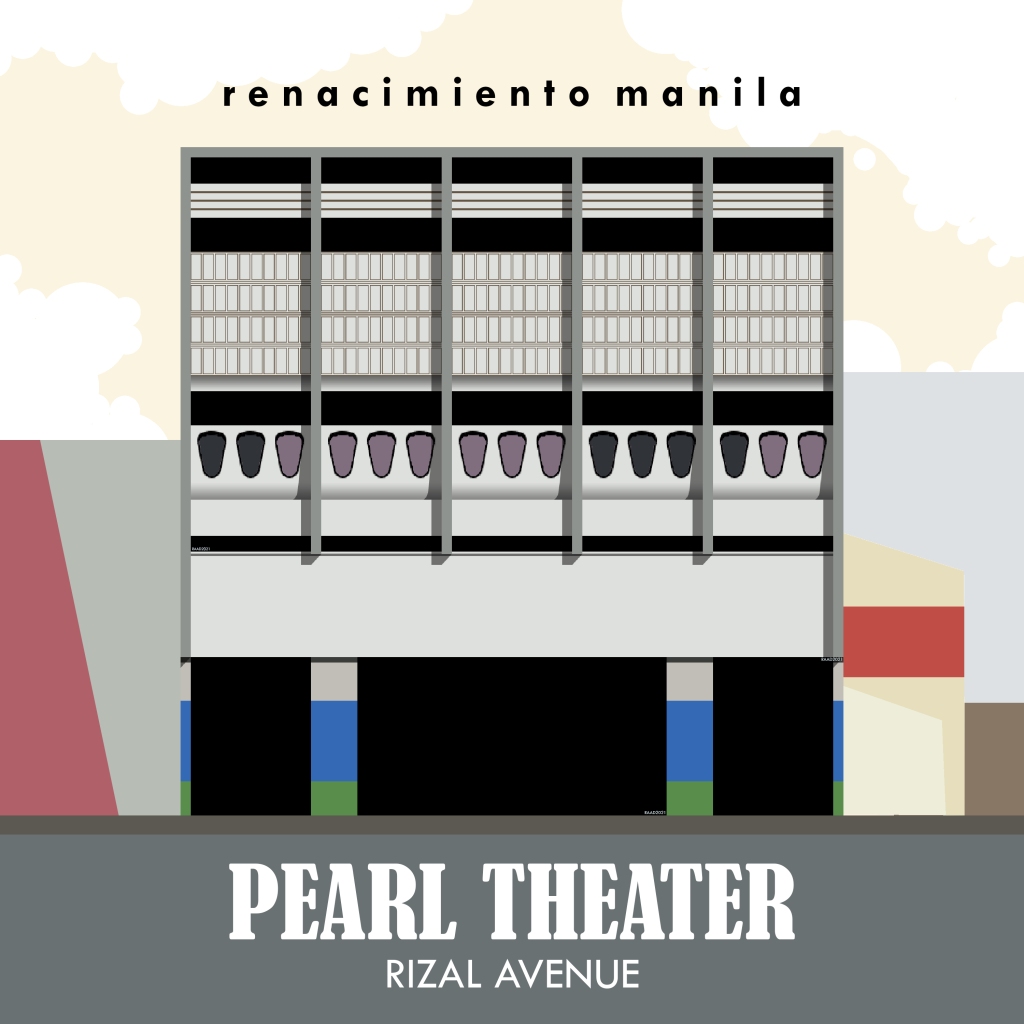

However, the movie industry began later in the 1900s where Filipinos started patronizing European and American-made films. Cinemas and movie houses were built and designed by significant architects during their time. Arch. Juan Nakpil designed theaters such as the Rufino-owned State, Avenue, and Ever cinemas along Rizal Avenue, Gaiety along M. H. del Pilar, and Capitol along Escolta. On the other hand, Lyric along Escolta, Life at Quezon Boulevard, and Dalisay, Capri, Scala, Galaxy, Forum, and Ideal along Rizal Avenue were some of the works of Arch. Pablo Antonio. Arch. Luis Ma. Araneta designed Times Theater along Quezon Boulevard.

Most movie houses followed the Art Deco, Art Moderne, and modernist architectural styles, utilizing architecture as a marketing tool to garner the attention and favor of Filipino patrons. Architecture also became a tool to exemplify societal status to appeal to members of the upper class. Cinemas became literal movie palaces, with embellished interiors and pompous lobbies as an events place for the social gatherings of the privileged in society. In fact, a city or area’s affluence can be denoted by the number of cinemas in that location.

Photo from Alex del Rosario Castro as cited by Isidra Reyes (2020).

During the Japanese colonial period, most movie houses featured propaganda material aimed at fostering friendship between the Filipinos and the Japanese. Other theaters did not heed to such demands, however. For example, Times Theater along Quezon Boulevard omitted propaganda material in favor of the inauguration of a ‘musical interlude’ on its stage. Succeeding this, other theaters followed suit as well.

Photo from the collection of John Tewell, Flickr (2016).

Photo from the collections of John Tewell, Flickr (2010).

After the Philippines became an independent country, the local cinematic industry developed further with the rise of different studios and the mass production of film after film. According to Baboo Mondoñedo (2020), four studios dominated the Filipino movie-making scene – LVN Pictures, Sampaguita Pictures, Premiere Productions, and Lebran International. These studios produced a total of 350 films during what came to be known as the Golden Age of Philippine Cinema in the 50s and 60s.

It was during this period that more standalone cinemas were built in Manila and other surrounding cities. They became products of innovation as well – for example, the first building to utilize escalators was the Roman Super Cinerama in Quiapo. Major thoroughfares such as Quezon Boulevard and Rizal Avenue were adorned with colorful cinematic lights as artistic and grandiose as the buildings themselves.

Photo from Lou Gopal of Manila Nostalgia (2015).

However, according to Karl Aguilar of the Urban Roamer (2013), the cinema industry in Manila began to decline in the 1970s with the rise of commercial areas in the likes of Ortigas and Makati. Along Rizal Avenue, the construction of the LRT Line 1 has reportedly contributed to the decline of said establishments, fostering a somber and disagreeable atmosphere within the area.

On the other hand, different factors such as the increase in popularity of shopping malls with their own cinemas, the availability of television for the average household, and the pirated DVD market has rendered standalone theaters obsolete as an entertainment hub for Filipinos.

With the decline of the standalone cinema business, some of the buildings in which these establishments used to be have been converted into commercial areas. Different (usually Christian) religious groups and a certain department store chain have utilized what used to be the cinemas’ spacious viewing halls for their respective interests. Others have unfortunately fallen into disrepair or abandonment. Cinemas that managed to survive mostly resorted to the screening of salacious films and the tolerance of prostitution within the premises, at least, before the 2020 pandemic.

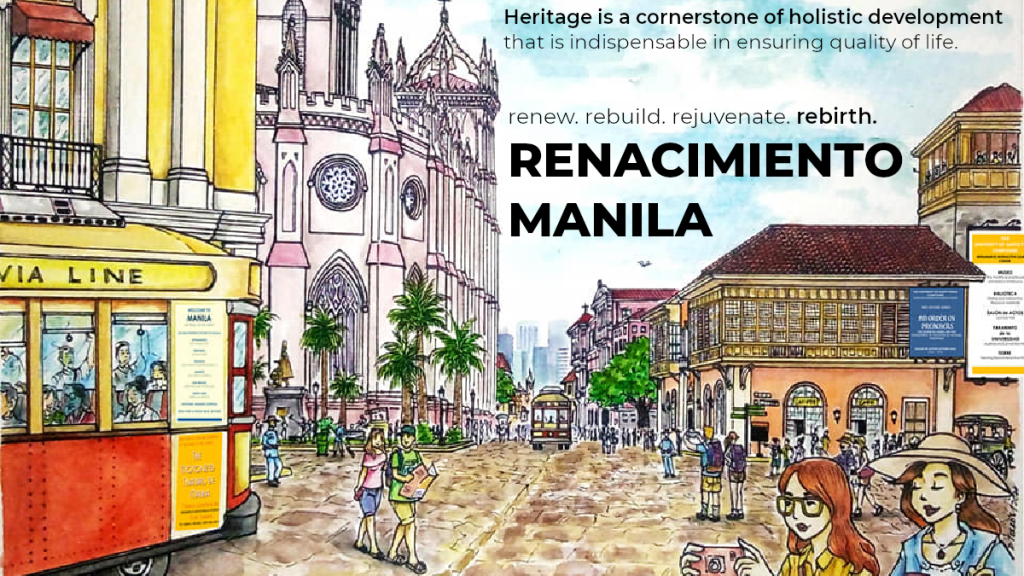

Here are the existing theaters we have in Manila as of March 2021. We have 25 theaters spread across Kalaw, Escolta, Ongpin, Rizal Ave., Quezon Blvd. and Recto Ave. The captions state their information and history. Photos courtesy by the author. All Rights Reserved.

The abandonment and mistreatment of existing standalone theaters serve as another reminder of the city and the government’s mediocre approach towards heritage conservation. Such structures were not only relics of a bygone era – rather, these also served as the hosts to significant events in cinema, the homes of prominent Filipino stars during the Golden Age, and the materialization of Filipino masters in the field of architecture.

With the standalone theater enterprise no longer feasible at the present, remaining structures may be repurposed into more practical typologies whilst preserving and incorporating what remains of their cinematic pasts. As with other heritage properties, support is needed from the government, such as with proper documentation of existing buildings and the reinforcement of existing heritage laws such as the Republic Act no. 10066, which classifies works of national artists and structures at least fifty (50) years old as presumed Important Cultural Properties (ICP).

Although Manila has witnessed the demolition and destruction of multiple heritage buildings in the past few years, it is never too late to be aware of the situation. As some of Manila’s heritage structures still exist, so are the chances that the remaining vestiges of the city’s past can be conserved and rehabilitated for both contemporary needs and future generations.

(A big thank you to Arch. Richard Tuason-Sanchez Bautista and Stephen John Pamorada for advice and additional information regarding this topic.)

Article, photos & digital art by Riel A. A. Diala. @abonymous_arts (IG)

Capitol Theater vector art courtesy of Diego Torres.

Renacimiento Manila. All rights reserved.

Sources:

Aguilar, K. (6 Apr 2013). Reminiscing the cinematic glitter: the old movie theaters of downtown Manila (Part I – An Introduction).

Retrieved from: The Urban Roamer

Aguilar, K. (13 Apr 2013). Reminiscing the cinematic glitter: the old movie theaters of downtown Manila (Part II: the theaters of Quiapo).

Retrieved from: The Urban Roamer

Aguilar, K. (21 Apr 2013). Reminiscing the cinematic glitter: the old movie theaters of downtown Manila (Part III: along Recto Avenue).

Retrieved from: The Urban Roamer

Aguilar, K. (01 May 2013). Reminiscing the cinematic glitter: the old movie theaters of downtown Manila (Part IV: at Avenida south of Recto).

Retrieved from: The Urban Roamer

Aguilar, K. (06 May 2013). Reminiscing the cinematic glitter: the old movie theaters of downtown Manila (Part V: the theaters north of Recto).

Retrieved from: The Urban Roamer

Dolor, D. (11 Oct 2015). Glory days of Times Theater.

Retrieved from: Philstar

Garcia, M. A. (13 Sept 2014). My Manila Movie Memories.

Retrieved from: Positively Filipino

GMA News. (20 Jun 2013). From palaces to ‘Serbis’: The fate of PHL’s grand movie theaters.

Gopal, L. (24 Jan 2015). Rizal Avenue – A street to love.

Retrieved from: Lou Gopal

Limos, M. A. (12 Aug 2020). Genghis Khan Was the Most Ambitious Postwar Film Ever Made in the Philippines. Esquire. Retrieved from: Esquire Mag

Mondoñedo, B. (18 Mar 2020). The Glory and the Glamour: Reminiscing the Golden Years of Philippine Cinema. Retrieved from: Philippine Asia Tatler

Rappler. (22 Oct 2019). FAST FACTS: The big 4 of Philippine Cinema’s ‘Golden Era’.

Reyes, I. (03 Feb 2020). From dream palace to ruins: the life and death of Manila’s grand movie houses. Retrieved from: ABS-CBN News

RKC. (17 Dec 2012). The glory that was Life. PhilStar Global.

Retrieved from: Philstar

Santos Knight Frank. (2017). Jennet & Lords Theater.

Sembrano, E. A. M. (06 Aug 2018). Cultural agencies reject demolition of Life Theater in Quiapo. Inquirer. Retrieved from: Inquirer

Tewell, J. (05 Jun 2010). Quiapo Church, also known as the Church of the Black Nazarene, was not war-damaged. Picture was taken looking north down Quezon Blvd., Manila, Philippines, 1945. Retrieved from: Flickr

Tewell, J. (22 Nov 2016). Times Theater, now showing: Bogart, Bergman, Casablanca (Casablanca starring H. Bogart and Ingrid Bergman, movie release date: 23 January 1943). Manila Philippines, last half 1940s. Retrieved from: Flickr

Tewell, J. (02 Feb 2021). Escolta Street, Manila, Philippines, 1941 or earlier. Retrieved from: Flickr

Video 48. (04 Feb 2009). Theaters in Metro Manila Circa late 60s and 70s.

Video 48. (03 Nov 2007). Remembering Roman Super CInerama.

Video48. (28 Nov 2010). “Ever Theater,” First Anniversary Souvenir Brochure/ 1955.

Villafuerte, S. (14 Jul 2020). In Manila heritage architecture struggles to survive. CNN Philippines. Retrieved from: CNN Philippines

The Renacimiento Movement. What, then, is the Renacimiento Movement? The movement is the core philosophy of the organization. It is founded on the reality that heritage is a cornerstone of holistic development and that it is indispensable in ensuring quality of life. As such, cultural revival is necessary for the promotion of heritage in the national agenda. Heritage should be driven by the people, regardless of race, gender, creed, or religion. This cultural revival can be achieved through the following ways: government support, the advancement of private initiatives, and the engagement of the people.

It is very saddening to see the decay of those works of art, giving them a ´ghostly´ appearance, a ghost that will continue to haunt those who failed in protecting our own architectural heritage.

LikeLike

you forgot miramar and maxim theaters near eastern and tandem theaters.

LikeLike

even though na hindi ko na abutan tong mgagadan cinema theater na ito maganda pa din tignan kahit sa ma pictures lang

LikeLike